The Cuckoo comes in April,

He sings his song in May,

In leafy June, he changes his tune,

And in July he flies away.

Traditional rhyme

The magical sound resounds over the lakes and scrubland: cuck-coo…. cuck-coo! I listen transfixed, but find it difficult to know from what direction it’s coming from or how far away it is. The unmistakable call of the cuckoo, the visitor to our shores who has always heralded Spring, a sign of mid April. Thrilling to my first cuckoo of the year, I feel it stirs ancestral memories in my being, and helps align my body clock with the seasons. The two note call carries incredibly far, a perfect musical interval, a descending minor third.

The cuck-coo sound envelops the early morning landscape in a mystery, the ethereal sound pervading it all. I don’t mind not being able to locate the bird himself, (and it is only the male cuckoo who makes this call) and I have the same reaction as Wordsworth did, when he wrote ‘To the Cuckoo’, referring to him as a ‘wandering Voice’, rather than a bird.

“O blithe New-comer! I have heard,

I hear thee and rejoice.

O Cuckoo! shall I call thee Bird,

Or but a wandering Voice?

…..Even yet thou art to me

No bird, but an invisible thing,

A voice, a mystery”

But this particular morning I suddenly see this invisible voice in the flesh, and another cuckoo too, quite close by me

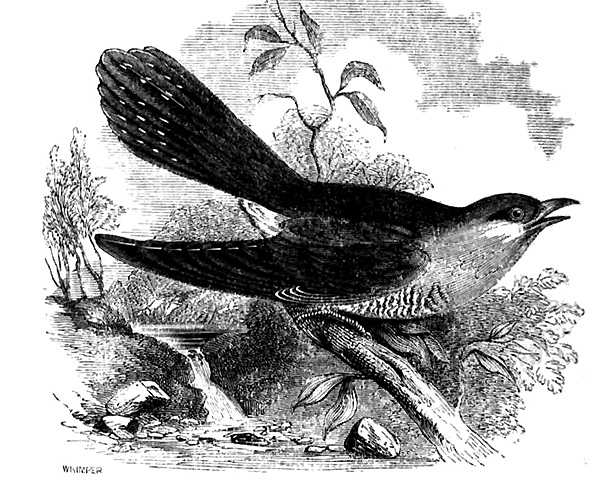

, and because they are engaging with each other, they don’t pay any attention to me on the path below. Usually they are quite shy and reclusive. The cuckoo doesn’t look as you might imagine; he or she is a largish blue grey bird with a long tail, a barred chest and pointed wings; more resembling a sparrow hawk than a typical songbird.

As with my annual nightingale pilgrimage, I feel the same urge to hear the cuckoo in spring, this mysterious being who has been so deeply woven into traditional culture for probably thousands of years, like the nightingale. The arrival of the cuckoo in many places was more significant than just the arrival of spring. Villages and towns had feast days associated with the time when cuckoos would first be heard locally. Cuckoo fairs have a history going back many centuries and there are still cuckoo fairs in a few villages in England, even though these days the cuckoo may no longer be heard in some of them. For example, the Downton Cuckoo Fair in Hampshire has records of a Fair as far back as 1249.

The cuckoo is an ancient part of mythology and culture worldwide and has probably generated more folklore than any other bird. Only a century ago English farmers thought it important not to sow barley until when the first call of the cuckoo was heard in order to ensure a full crop. It was widely believed in many parts of Europe that the number of repeated calls of the cuckoo reflected longevity in the person who counted the calls.

In Ancient Greece, Pliny the Elder wrote of cuckoos having a magical ability to protect from pestilence with their calls, while it was Aristophanes’ play “The Birds,” which is the source of the “cloud cuckoo land,” the birds utopian city-in-the-sky.

In the Celtic tradition, cuckoos were considered to have the ability to travel between worlds and were often associated with death and the afterlife. The call of the cuckoo was said to have the power to summon the dead.

In Indian mythology, cuckoos are highly regarded because their arrival corresponds with the beginning of the monsoon season. Therefore, these birds often symbolise the dawn of a new year, fertility, and hope.

Unfortunately the cuckoo is disappearing from much of England and it grieves me that children will no longer grow up hearing this symbol of our felt connection with the seasons. Cuckoos specialise in eating hairy caterpillars which are toxic to most other birds and hairy caterpillars are sadly in huge decline in our overmanaged, oversprayed farmland. So it is because of this and increasing pressures from the climate and ecological crisis, that cuckoos are becoming a rarity that few people will even hear today throughout much of England.

Each spring, I like dawn walking in the reclaimed gravel pits and scrubland that now make up a 30 mile long linear regional park extending northward from inner East London, where nature has been allowed to return in its exuberance and lushness. Such regenerating rough thickets, emerging woodland, reedbeds, lakes and islands are a great example of rewilding and there is more biodiversity here than in the majority of our intensively managed and sprayed countryside. Here cuckoos still cling on, as do nightingales, who require unmanaged scrubland to live.

Cuckoos are well-known brood parasites. They don’t build their own nests, but rather the females lay their eggs in other birds’ nests, especially reed warblers in my local area. The female cuckoo looks for a suitable nest, and when the hosts aren’t looking, she removes one of their eggs and lays her own egg in its place. The baby cuckoo, after hatching, pushes the hosts’ eggs or babies out of the nest, and then eats all the food brought by the poor surrogate mother reed warbler.

Where the cuckoo goes in winter has always been a mystery. It’s only in the last few years that researchers from the BTO (British Trust for Ornithology) have been able to fit very lightweight trackers to cuckoos and learn that they fly 5000 miles south right across the Sahara to the equatorial rainforest of the Congo. They took the unusual (for scientists) step of giving each cuckoo a name and letting anyone track the cuckoos’ movements throughout the year on a map on the web.

I could follow the movements of ‘Jac’, one of the tracked cuckoos who, having spent months deep in the rainforest of the Congo, suddenly flew a thousand miles west to Nigeria on 22nd February this year and then flew further west to Guinea on the way back to Europe. Jac’s migration had started and the Spring urge was tangible in his new movements. Here was I sitting in wintery February London connected with Spring mysteriously stirring in the breasts of this bird 5000 miles away in equatorial Africa.

After feeding up, Jac flew north over the Sahara to southern Spain, arriving back in his home area of North Wales in mid April of this year.

I was deeply moved by entering into Jac’s epic journey, an expansion of my emotional connection with the vast interwoven web of life. Kinship with the cuckoo.

For me It brings to mind writer Sophie Strand’s notion of ecological intimacy:

“The being, the ecosystem, the species that sparks your curiosity and softens your heart is a portal to the whole world. Befriend and court and woo one single being, one single spot….Trust that these beings want your love and attention and if you follow that attention it will turn into a doorway that leads into a much wilder, more creative world of kin. What you love, loves you back. Ecological embodiment is just a fancy way of saying, “Love something with your whole body.”