Reasons to be Cheerful

With all the bad news of recent times, it’s easy to feel that collectively we’re going backwards and that the planet’s living systems are heading in the direction of terminal decline. Environmentalists can lose heart that the liveable advances that have taken so much struggle to secure, are often now being rolled back. Climate activists are being increasingly criminalised by Western governments, who still follow the dictates of the seemingly all powerful fossil fuel lobby. Activists can feel like the boy holding his finger in the dyke to hold back the flood of disaster, but unfortunately without the good ending of the folk tale.

While this is unfortunately too true for my liking, there’s a very practical environmental movement gathering force under the radar which is a very real counter to all this: And that is Rewilding. I recently attended the two day Cambridge 2025 conference on Rewilding, bringing together people and projects from around the world.

Whether you call it rewilding, regeneration, restoration or wilding, these projects, ranging from the very small to the gargantuan, are quietly forging ahead in parallel to the status quo.

Instead of attempting to fight against the tsunami of bad stuff, which is often only possible to a disappointing degree, as I mentioned before, rewilding is quietly going ahead all over the world, building a better future for all beings, human and non human.

Many attendees of the Cambridge Rewilding conference were scientists and field workers deeply engaged in projects. I’m not attempting to report on any of the detailed science, but writing more to convey my sense of an overview of the whole phenomenon, illustrated by a few examples of the very many projects on show there. I had attended the inaugural Cambridge Rewilding conference in 2019 when rewilding was far less known to the general public and was seen then as quite radical, and I wanted to see the developments.

The goals of rewilding include Increasing biodiversity, restoring natural processes, reducing the effects of climate change, and reducing the effects of the global extinction crisis.

Today there are numerous rewilding organisations, although the word ‘rewilding’ was only added to the dictionary in 2011. It was popularised by George Monbiot’s 2013 book, ‘Feral’, which advocated the idea of letting nature manage itself. Alister Scott, Co-director of the Global Rewilding Alliance said that for him, ‘Rewilding is hope’. Rewilding is not about leaving civilisation but about enhancing it. We can’t thrive unless nature thrives.

Knepp scene

In the UK, the poster child for Rewilding has been the Knepp estate, where a very large unproductive farm in Southern England, sitting on clay which was a quagmire in winter, and baked hard like concrete in summer, was allowed to return to a more natural state with the cessation of regular farming. Its transition to a wilded state has been measured year by year and has resulted in an extraordinary increase in biodiversity with rare UK species like Nightingales and Turtle Doves thriving. I personally have visited Knepp a few times and experienced this natural evolution over the years. The emblematic white stork, now established around Knepp after an absence in Britain for hundreds of years, captures the public’s imagination.

Large herbivores such as wild cattle, ponies and pigs, with their grazing, trampling and rootling, keep the mosaic of habitats in balance, enabling maximum biodiversity. Rewilding is not the same as merely leaving land alone. In Knepp, for example, like many rewilding sites, there are no natural predators such as wolves to control the numbers of large ungulates, which left unchecked would eat all the vegetation and eventually starve. So culling is needed by human intervention and in Knepp’s case provides high quality beef, pork and venison, which they sell.

Knepp is largish, but on the absolutely huge side of rewilding projects, the Director of Rewilding Chile, Carolina Morgado, conveyed what was possible with the string of National Parks created down the length of Chilean Patagonia – many millions of acres – linking and restoring habitat. The grasslands were previously worn out and degraded by a century of overgrazing by sheep and had become economically unviable. Facilitated by enormous philanthropic gifts from the Tomkins, founders of outdoor brands Patagonia and North Face, and working with the Chilean government and creating local employment, eco tourism and retraining for local people, their achievements are astounding. The rewilded lands have become ‘engines of the local economy’ according to Caroline Morgado, and succeed in getting their government onboard by demonstrating that it is a good financial investment.

One of the developments I find most interesting and heartening is the shift from old mindsets of just trying to conserve fragments of nature or focussing on single iconic species. This view tends to see nature as something separate from us to be set aside like a kind of giant bell jar or game reserve. Indigenous peoples were sometimes forcibly removed from African conservation zones and such practices have colonial overtones, as well as reflecting these old attitudes of estrangement from the living world.

Now it’s becoming more widely recognised that human beings are an integral part of ecosystems as well as non human beings, and that rewilding works when people feel – and are – part of the plan. Wilderness includes people too.

This was illustrated vividly for me at the conference by hearing firsthand the story of Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, a huge 4000 sq km area that had been the site of the terrible Mozambique civil war which finally ended in 1992. The wildlife had been decimated by the opposing armies and it was almost a ground zero situation. Yet it has been transformed by nature’s inherent resilience coupled with careful human intervention and help. Now it is again an amazingly rich habitat with local people fully involved and feeling that this land of theirs is precious and to be respected. Local people have been employed with 300 rangers among the park’s 1700 employees – and we heard that the best rangers were those who were previously poachers. Education and health care is part of the park’s remit, and productive coffee growing on the park fringes provides better employment than ever before. The park has become a hub for scientific research and for the training of local people. I was very impressed by what had emerged from a scenario which only three decades previously, had been utterly disastrous. Rewilding can be win-win.

Frans Schepers of Rewilding Europe spoke of large landscape nature recovery in Europe and what has been learned from the 11 large scale projects all over Europe from the Danube Delta to Swedish Lapland, to the Iberian Highlands in Spain, that Rewilding Europe is involved with.

Being a conference held in the UK, there were many UK based projects featured, and this is especially needed since Britain is actually one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world.

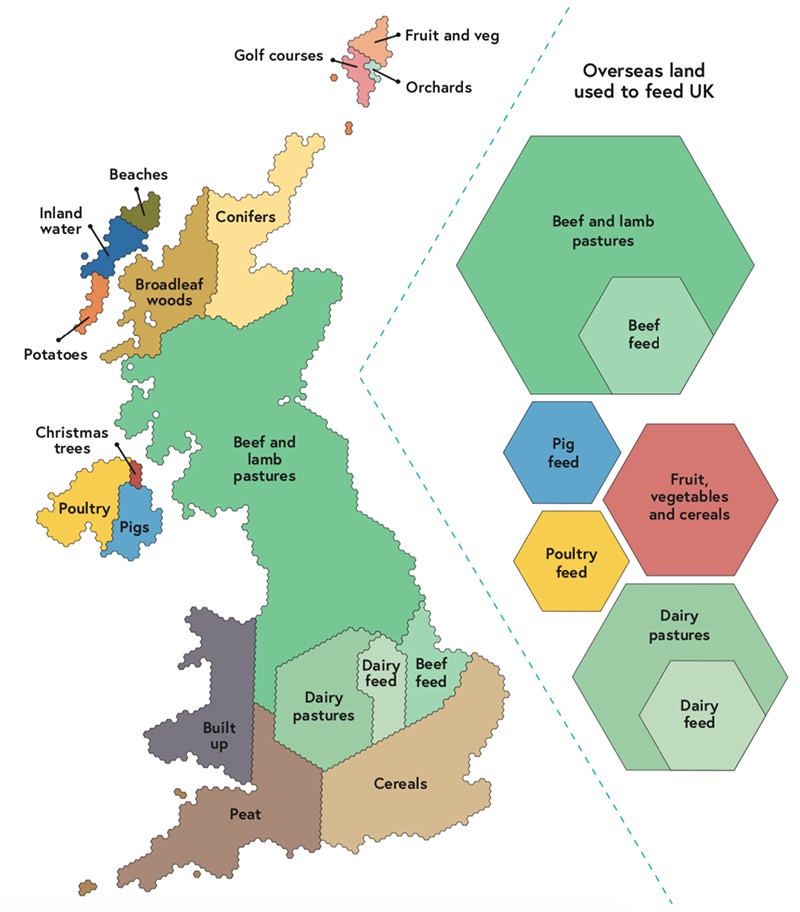

Land use in Britain by proportion – (not the geographic distribution!)

With much more than half of the land in Britain used for animal grazing (see diagram above) including a large extra amount of land in other countries being used to grow feed for UK livestock ( eg. from clearing rainforest to grow soy for animal feed), it’s clear that a significant reduction in meat consumption could free up an enormous amount of land in even a small country like the UK. This land could be rewilded with great benefit to wildlife, human health and well being and bringing big reductions in carbon emissions.

Since more than half of us now live in urban environments, urban projects are vital too, and schemes were discussed regarding greening cities and streets. It is clear that rewilding is not just about restoring ecosystems but also about reconnecting people with nature; the link between human well-being and healthy, wild landscapes being very well established.

Coming even closer to home, another aspect covered was the rewilding of the microbiome of our guts. It’s now emerging that reduced contact with diverse microbial communities in urban environments may contribute to immune dysfunction and related disease. Rewilding degraded ecosystems could potentially restore at least some microbial diversity, possibly reversing these effects.

A beaver dam in West London

There were many smaller inspiring initiatives and one which I love is the reintroduction of beavers to Britain after being exterminated centuries ago. They are a classic keystone species: ecosystem engineers who create new habitats enabling much richer biodiversity while retaining water with their damming, which reduces flooding. Remarkably, beavers are now living in a marshy site in West London in Zone 4 on the Tube line, and doing well.

All this is not about going back to anything; it’s not the impossible attempt to recreate the past. Nature is not nostalgic. Life is creative and resilient and what emerges will always be a new expression. Rewilding Britain has a strapline: Think Big. Act Wild.

It seems to me that ultimately, first and foremost, we need to rewild ourselves.